Charles and Ray Eames left us with dozens of iconic masterworks, from classic furniture and textiles still in production some 70 years after their introduction to pioneering films that broke new ground in the way information is presented and digested. Part of the magic was their iterative process, with each completed design building on previous work and setting the stage for the next. You’ve seen the Eames Lounge and Ottoman, the shell chairs, and the Surfboard table hundreds of times, so come with us on an Eamesian “crate dig” as we rummage for the deep album cuts, oddities, and rarities to fill in the blanks between their greatest hits.

The 3473 Sofa had some truly innovative features—like an aluminum frame whose cross section graduated from round to elliptical. Its overall form and construction alluded both to the Eames Sofa Compact and the Eames Executive Chair. The Sofa Compact struck a chord because it was like a post-war hot rod: its structure exposed and straightforward, its demeanor youthful and mobile. But, let’s be honest, the upholstered seat and back cushions on the 3473 Sofa look, just a bit, like a couple of old-school swimming pool floats. Eames Demetrios, Charles and Ray’s grandson and director of the Eames Office, calls the sofa “a transitional piece, and it’s valuable as such. The last thing on Charles and Ray’s mind was what something looked like—they were more concerned with how it solved the problem.” Herman Miller made the 3473 from 1964 to 1973.

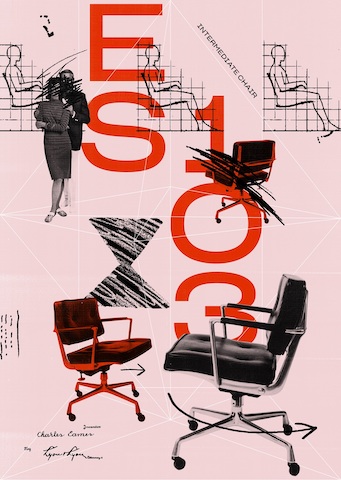

The Intermediate Chair from 1968 is similar to the 3473 Sofa, in that its DNA is aligned with a classic design that preceded it—the Eames Executive Chair. Comfortable without feeling stuffy, this chair is just as solid as its more imposing forebears, but the vibe isn’t as sedentary. The open lower back and the tilt swivel mechanism on the pedestal base reinforce the idea that even though you’re sitting, you’re still on the move. Back in the day, with the Intermediate Chair under you and a pack of Pall Malls at your side, you could knock out reports for eight hours straight. Designed for the commercial office market, it was a solid chair, but the introduction of the popular Soft Pad Chair led to it being discontinued in 1973. A true nod to its importance: the Intermediate was the chair that Charles used at his personal desk.

The EC-127 was a variation of the DCM-L (Dining Chair Metal, Library version). The main innovation here was the substitution of fiberglass-reinforced plastic for plywood, allowing the introduction of a new shock-absorbing rubber and metal mount. This new detail, which maintained the dramatic cantilevered interface of the metal frame while avoiding the pitfalls of a glued connection, proved valuable enough to be used in most Eames plastic chairs for years to come. While most of America was high-fiving the moon landing in 1969, the engineers at the Herman Miller Tech Center were high-fiving the shock-mount connection. The EC-127 was more durable and less expensive to produce than the DCM, which resulted in strong sales in the library, school, and hospital markets in the US. Its back legs were also ¾" longer than the DCM, to allow for a more ergonomic reading posture.

“Charles and Ray thought of systems like Contract Storage as tools to perform a task,” says Demetrios. “Think of a hammer—you admire a hammer not for looking pretty, but because it does a good job of driving nails.” Less hammer than Swiss Army Knife, the Eames Contract Storage system featured an arrangement of furniture items: bed, desk, and closet. Designed for student dormitories—at a time when universities and institutions were the major consumer of Eames seating—the system was orderly, well-crafted, and responsive to the needs of students and maintenance workers alike. For fans of Charles and Ray’s work, there’s a lot to nerd out on here—scratch-resistant embossed fir plywood, polished cast aluminum hardware, innovative continuous aluminum hinges, wire shelves and drawers, a built-in light, and a handy tackboard. All of it in motion and interconnected. It was all about achieving order in the midst of a college student’s chaotic life—and maybe that’s what did it in. Its production (1961–1969) just happened to coincide with a decade more closely associated with students looking to disrupt order, not contain it. That said, Demetrios muses that Contract Storage could still today help people organize their increasingly compact homes and apartments.

You can’t knock the Loose Cushion Armchair for lack of hustle. The technique of injecting polyurethane foam into a mold—with the actual polyester seat shell forming the other half of the mold—had been around for only three years when this chair was introduced in 1971. The Loose Cushion Armchair was an attempt to build on the popularity of the ubiquitous Shell Chair, with additional comfort. Here, the foam injection process at the time didn’t allow for a significant increase of foam at the seat, so the introduction of a loose cushion with a different level of “give” helped to make up for it. The end result was indeed comfortable—but caught between the office and the home, the chair never quite gained traction.

The Incidental Table, or IT-1, was intended by the Eamses as a kind of furniture stem cell for post-war modern families. It could be a side table, looking sharp next to your LCW chair. Or, it could be your kid’s desk, providing a stylish yet durable surface for her to assemble a jigsaw puzzle. Or, it could even be a makeshift seat when you hosted a cocktail party and were light on chairs. The IT-1 was a nice, sturdy, portable table, with its roots in Charles’ 1946 so-called “one-man” exhibit, New Furniture Designed by Charles Eames at MOMA. Perhaps in the end, the public saw it as a card table—and it couldn’t compete with cheaper card tables—so it went out of production in 1964. Our crate dig resulted in an interesting sidebar from Demetrios: “The artist Tony Rosenthal was a friend of my grandparents, and he loved the folding tables. He hung one on his wall as a piece of sculpture with the underside showing.”