Balthazar Korab arrived in Michigan in 1955, during what was intended as a short visit to his in-laws with his first wife, the American-born Sally Dow. Trained as an architect in his native Hungary, and later in Paris, Korab was eager to find work. Surprised to discover that his in-laws lived near the office of Eero Saarinen and Associates, he cold-called the firm and was granted an interview with Saarinen and his design principal, Kevin Roche. At the end of a conversation about designs Korab made during his architecture studies, Saarinen offered him a cigar and a job with a starting wage of $2.75 per hour, then asked him to return after lunch that same day. Korab immediately began working on several projects.

Korab’s skill with a camera quickly caught the attention of Saarinen, and before long he was responsible for integrating photography into the firm’s design-development processes, while also capturing large-scale models and full-scale building mock-ups. At first he documented the development and construction of the IBM Manufacturing and Training Facility (Rochester, MN), the Miller House and Gardens (Columbus, IN), and the TWA Flight Center at Idlewild Airport (later John F. Kennedy International Airport). As his responsibilities in the office expanded, he would eventually be commissioned to shoot iconic Saarinen projects, including Dulles International Airport; the United States Embassy in London; Deere & Company’s Moline, Illinois headquarters; and the St. Louis Gateway Arch. He recorded the structures under construction and comprehensively documented completed projects for publicity in leading design journals and architecture publications. During his time in the office (1955–1958), Korab’s contribution as an architect to the development of Saarinen’s most complex and technically challenging projects was indispensable, and in return he acquired a deep understanding of the completed buildings. Because of this, Korab was able to photograph the exploratory geometries, material innovations, and interplay of light and shadow that typifies Saarinen’s designs in a manner that now seems synonymous with their mythic status.

Eero Saarinen & Associates, TWA Flight Center, New York Idlewild Airport (now John F. Kennedy International Airport) (Queens, NY, 1956–62). Photo: Balthazar Korab, 1964.

As his career progressed, Korab’s widely circulated images garnered the attention of numerous architects and designers who began their careers in the Saarinen office—César Pelli, Paul Kennon, Robert Venturi, and Gunnar Birkerts, among others—and those beyond the Saarinen circle, including Mies van der Rohe, Minoru Yamasaki, and William Kessler. Through this work, Korab became one of the most sought-after photographers by magazine editors, advertising agencies, and a network of public relations firms that populated the Detroit area, earning him commissions for a vast array of subject matter beyond the mid-century modern design with which he is most associated—industry brochures, automobile styling designs, trade publications for material manufacturers, and industrial fabrication facilities.

Herman Miller Eames Multiple Seating brochure with photography by Balthazar Korab from 1965.

Korab’s assignments gave him a front row view of a significant transformation in Michigan’s design scene. During Korab’s tenure with Saarinen, the state was characterized by what Monica Korab, Korab’s second wife and business partner for over 50 years, described as “a unique cultural time zone.” Drawing from numerous design fields, designers of this era developed innovative fabrication technologies, advances in material sciences, and new production processes that influenced everything from the furniture and industrial design production of western Michigan—home to Herman Miller among others—to the postwar exuberance of the automobile industry centered in and around Detroit. This flurry of design innovation, combined with the demand of an industrial and consumer culture eager to remake the home front, well positioned companies like Herman Miller to transform their products as well as the materials and processes used to design and manufacture them.

Eames Educational Seating by Herman Miller installed at the Chicago Circle Campus of the University of Illinois. Photo: Balthazar Korab, 1967.

The evolution led to a shift in photography, evident in a selection of Korab photographs recently uncovered in the Herman Miller Archives. In Korab’s images of the Tandem Sling Seating designed by Charles and Ray Eames (1962) for Herman Miller, we see him matching the sinuous ergonomic designs of the aluminum-frame chairs with the formal dynamism of the airport architecture for which they were made, in particular the Dulles International Airport. Korab, having worked in the Saarinen office when Dulles was under development, had gained insights about the project that helped guide his approach to documenting the architecture and interiors: from the swooping curvature of the roof structure to the details of the “Sling” furniture arranged throughout the open concourse.

In Korab’s Catenary Group portfolio from the Herman Miller Archives, we again see his knowledge of design guiding his composition of the shot to emphasize the material, form, and spatial characteristics of the furniture-as-architecture.

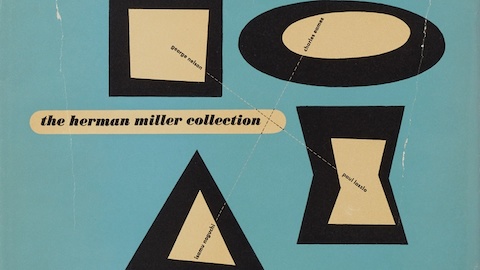

George Nelson, the Director of Design at Herman Miller from 1945 to 1971, and his associates designed the Catenary Group in 1963. That he had sought out Korab to photograph the collection was a logical choice, since Nelson was instrumental in rethinking how product catalogs embodied design principles, an initiative that would help direct the growth of company for decades. In the foreword to the first edition of The Herman Miller Collection, Nelson emphasized the principle of interdisciplinary design when he wrote that with the “architectural approach to any design problem, and particularly that of furniture … the problem is never seen in isolation.”

In one noteworthy photograph of the Catenary Group, Korab situated the collection within the Minoru Yamasaki–designed Regional Sales Office of the Reynolds Metals Company (Southfield, MI, 1955–59) as a way to highlight the harmony between the pieces and their context. The building itself transforms our impressions of steel and aluminum through an expression of lightness that counters the weight of their industrial origins, and, together, the design qualities of the furniture and its setting are echoed and highlighted in a manner far greater than if they were presented independently.

Korab’s photograph of the Catenary Group, designed by George Nelson for Herman Miller in 1963.

Korab was more than an architect and a photographer; his body of work reveals that he was also a cultural anthropologist of sorts. He approached his subject matter with the belief that architecture is inseparable from the people, places, institutions, and cultures within which it is created and by which it is shaped. And while Korab became most widely known for his images of iconic mid-century modern buildings, his career-long efforts documenting the design legacy of his adopted home Michigan often led to some of his most enduring and varied subject matter—from vernacular buildings and historic sites, to large industrial landscapes and anonymous structures found in small villages and rural towns. As Monica Korab has noted:

Balthazar, a perpetual foreigner in a strange land, was far more enthusiastic with this vernacular and industrial subject matter than many of his other projects at the time, because it went beyond the architecture into a much broader expression of a particular culture. Everything was new and worth examining, and I think he saw something in America—an explosive push to build differently from his European roots.

For Korab, architecture and design offered much more than just static objects to be idealized through the frame of a camera. In his own words, “The story prevails in my approach to photography; the feelings, responses to a place, the message. And photography,” he continued, “is a very important way of creating a record of the transformations experienced throughout the cultural life of a place.” It was through this lens that Korab approached one of his most comprehensive portfolios in the Herman Miller Archives.

In 1983, the Houston-based architecture firm Caudill Rowlett Scott (CRS) commissioned him to document the newly completed Herman Miller Seating Manufacturing Plant in Holland, Michigan. By the time of the assignment, Korab was already years into a multi-year project commissioned by the Michigan Society of Architects (MSA) to create a comprehensive photographic survey of significant buildings across the state. Korab broadened his interpretation of “significant works of architecture” to include industrial buildings, anonymous structures, and working landscapes built to support the lumber, mining, agricultural, and manufacturing industries, which highlighted the state’s transformation from a largely agricultural economy into the center of modern design in America.

Looking at Korab’s survey of the Herman Miller Seating Manufacturing Plant, we see him drawing upon the sensibilities that he developed documenting the idiosyncratic buildings and sites in his survey of Michigan architecture: from the agricultural landscapes of western Michigan, to the industrial infrastructure of the Rouge River, to the modern commercial buildings of downtown Detroit.

Herman Miller Seating Manufacturing Plant in Holland, MI. Photo: Balthazar Korab, 1983.

Michigan was the crucible for the intersection of agrarian craft and industrial force, a subject matter that was a recurring theme for Korab. The photographer clearly understood how images can elevate our awareness of the seemingly ordinary spaces, objects, and materials that shape our daily existence, and in doing so he crafted a vibrant portrait of Michigan’s multifaceted design narrative. Combining the exactitude of a forensic detective with the grand narrative breadth of a documentarian, he did the same for the monumental structures that redefined architecture during the second half of the twentieth century.