Billy Wilder—the Hollywood director of classics like Some Like It Hot, The Apartment, and Double Indemnity—loved to nap. Nothing like 20 winks between lunch and dinner to keep the creative juices flowing. His problem was making sure that his catnaps didn’t lead to deep, disruptive slumber. Lucky for Wilder, then, that his long-standing friendship with Charles and Ray Eames—perhaps the era’s most lauded furniture designers—yielded the exquisitely elegant and perilously narrow Eames Chaise. Designed expressly for Wilder (he was the recipient of the first production model—a gift from the Eameses) to use as a perch for his brief but frequent afternoon naps in 1968, the chaise is just 18-inches wide, and, as Wilder noted, “If you had a girlfriend shaped like a Giacometti, it would be ideal.”

Charles once said that he learned more about architecture on Wilder’s sets than anywhere else. And though the montage sequences he did for Wilder’s 1957 documentary The Spirit of St. Louis and the opening credits Ray designed for Wilder’s 1957 film Love in the Afternoon speak to a rich friendship and collaboration, and they also show that the creative peregrinations of the Eameses at some point had to move behind the camera.

Wilder and a coterie of other Hollywood friends served as something of a bridge between the worlds of design and film—a bridge that, by the end of their careers, Charles and Ray crossed scores of times.

© Eames Office, LLC

The Eameses have over 125 films to their credit, with film, installations, and information design occupying the bulk of their output in the 1960s and 70s. “Projects changed in emphasis and the office moved away from furniture as a full-time occupation to projects in which the transmission of information was the most important factor,” recall John and Marilyn Neuhart, frequent collaborators with the Eames Office, in the book Eames Design, which they coauthored with Ray. For the affable Charles and Ray, who lived perched above the sea in the home they designed in the Pacific Palisades neighborhood of Los Angeles, their exploration of filmmaking was as much personal as it was professional.

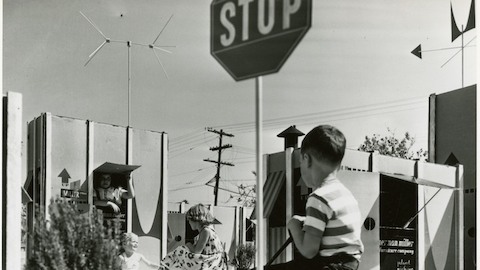

Philip Dunne, a writer, director and producer for Twentieth Century Fox, was a client and friend, and planted the seed for Charles and Ray’s first forays into filmmaking. The couple wanted to use his 16mm film projector—which he lent them while on location in South America—so they rented a camera and produced their first film, Traveling Boy in 1950. The film was made using wind-up toys, circus posters, and drawings by Saul Steinberg. Though rarely seen publicly, the rough experiment served the basis for several subsequent Eames toy films like Toccata for Toy Trains (1957) and Tops (1969), that took everyday objects, toys, and folk rituals as a recurring topic of interest. Often presented as close visual readings and set to an instrumental score by Elmer Bernstein—he composed the music for The Magnificent Seven, The Ten Commandments, To Kill a Mockingbird, Ghostbusters, and many others—these short films imbued everyday objects with a sense of playful wonder and appreciation.

© Eames Office, LLC

Film was a natural evolution for the Eameses as it presented a natural and deft vehicle to communicate their panoply of ideas and to experiment with technology and communication. Charles had been a photographer since discovering his father’s camera equipment as a child and the allure of film—made with technical tools, easily reproducible, communally experienced, and distributable on a mass scale—shared startling likenesses to the couple’s furniture designs. As Charles explained in an extensive 1970 interview with Film Quarterly, the medium was a means to connect: “They’re not experimental films, they’re not really films. They’re just attempts to get across an idea.”

Those ideas were characteristically diverse and ran the gamut from pure visual play to close readings of the world around us, to educational, and even political films.

“When we look at the night sky, these are the stars we see: the same stars that shine down upon Russia each night. We see the same clusters, the same nebula, and from the sky it would be difficult to distinguish the Russian city with the American city.” So begins Charles Eames’s narration in Glimpses of the U.S.A., a larger-than-life installation the Eames Office produced for the United States Information Agency. Projected across seven screens for the American National Exhibition in Moscow in 1959—the first USSR-USA cultural exchange—the film was a grand-scale realization of the Eames Office’s fascination with moviemaking and a collaboration with then-Herman Miller design director George Nelson.

© Eames Office, LLC

In some cases, their film work also served their business.

In 1954, the Eameses produced S-73 (Sofa Compact) for Herman Miller, beginning an extensive body of film shorts for the company that would continue for more than 20 years. Ostensibly made as a sales tool to demonstrate and inform both its staff and users how to unbox and assemble the neatly flat-packed Eames Sofa Compact, S-73 achieved its predictably Eamesian charm and visual sophistication using friends of the Eames Office and Herman Miller staff as the “cast.”

Some of the Eameses’ most prescient musings on modern design, in fact, emerged from these quippy short films for Herman Miller. “The details are not the details, they make the product,” is one of Charles Eames’s more famous dictums on design and comes from the product film ECS, a 1961 short on Eames Contract Storage, a furniture system designed for student dormitories. The pleasure and irony, of course, is that though the ECS eventually fell out of production and use in dormitories, its memorable description of “the details” is an enduring aphorism in the design trade. In the film Design Q and A (1972), which is at the top of this article, Charles continues to elucidate his philosophy with oft quoted lines like: “One could describe design as a plan for arranging elements to accomplish a particular purpose.”

© Eames Office, LLC

Regardless of whether they were used as a sales tools or explorations of the world around us, the Eameses were experts in their craft. The films, as a body, are sophisticated, visually rich, and technically complex. At times, Charles and Ray might mirror the avant-garde jump-cuts modish in the French New Wave; at others they crib the intimate photographic scale and perspective of a slideshow travelogue; and in others still, they offer the diligent exactitude of a rapid-fire art history lecture given by an enthusiastic instructor. Indeed, the multimedia slideshow was a common format that Charles would return to and apply with vigor, particularly in his Charles Eliot Norton lectures at Harvard University in 1970.

© Eames Office, LLC

The most iconic of the Eames films, however, is easily Powers of Ten, a 1977 short that both visualizes and enumerates the importance of scale and found a ready home in science class curriculums across the country. Like a lasso through time and space, the nine-minute film takes the viewer on fantastic voyage out to the edges of the universe, and into the sub-atomic depths of the human body. Made just five years after the famous Blue Marble photo was captured from outer space, the film, like both, offered a vastly new way of looking at the world.

Nearly 40 years after Charles and Ray’s last film—the 1979 A Report on the IBM Exhibition Center—the notion that their films are merely another medium for design, and that design is itself a form of communication, are still edifying, arresting, and pleasurable. And in the words of Charles himself: “Who would say that pleasure is not useful?”

Related Articles

-

Serious Fun - Herman Miller

Taking inspiration from the humble cardboard box, Ray and Charles Eames created toys and furniture to spark the imaginations of kids and grown-ups alike.