Hunter, gatherer,

collector

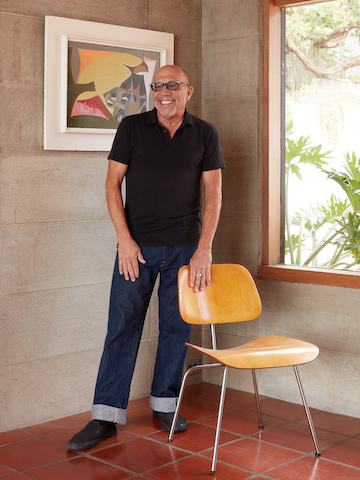

Steve Cabella has been amassing Herman Miller vintage for decades. We pay a visit to the ultimate fan at his 1935 William Wurster house overlooking the San Francisco Bay to hear his stories.

Written by: William Bostwick

Photograpy by: Mariko Reed

Published: April 26, 2024

Steve Cabella’s Monark bicycle leans against a concrete block wall outside his home, a William Wurster-designed single-story on the edge of the San Francisco Bay in Point Richmond. The house and the bike are the same age—built in 1935—and both work just fine. “It goes, it turns, it stops—of course, I still ride it,” he says.

A voracious and longtime collector, Cabella spends his time digging through archives and organizing exhibitions—12 and counting—like “Ray and Charles in Hollywood,” about the designers’ connections to the film industry. The Modern i, his furniture outpost in San Anselmo, was a destination for midcentury fans. He closed the physical location in San Anselmo, but he keeps collecting stories. As the tide laps against the seawall underneath, Cabella tells one about his bike, and his favorite material, aluminum.

“I love aluminum,” Cabella says. “Monark used aircraft grade aluminum tubes—it was what was available at the time. It was easy to get, it’s honest, simple, malleable. It can be anything you want but it always looks like what it is.” He looks at the bike for a bit, low-slung maritime sun flashing off the polish. “I like it for the same reasons they like it.”

At Cabella’s house, the past is present. The collector decked it out in midcentury gems from his personal archive. “They” are iconic designers George Nelson, Charles and Ray Eames, Alexander Girard, and others. He talks about them in the present tense, and their spirit is palpable, a reverberating echo like the waves beneath the house. Cabella has spent his life listening to voices few others hear.

He started collecting early, going to flea markets as a teenager looking for good design, or good stories, or anything other than the austerity of his childhood in Marin. Cabella was always a few decades behind—in the late sixties, he was dressing Victorian, lining his room in turn-of-the-century fabrics, throwing parties where correct period dress was enforced “down to the watch in your pocket.” His high school yearbook photo shows a young man dressed like a nineteenth-century dandy. “Authenticity is a kind of respect.”

“Objects hold stories. But you

need to take time to sit and study

each detail. You need the heart to

pay attention.”

By the late seventies, when he opened his shop, the Modern i, Cabella was exploring Art Deco. It was trendy to collect at the time, and had an appeal—“strong aesthetics is an instant story.” But Deco was expensive; its classy curves reserved for those who could afford them. “It wasn’t for people like me.”

The 1935 house, designed by William Wurster (namesake of the architecture school building at nearby University of California, Berkeley), overlooks the San Francisco Bay toward Marin.

Midcentury design, on the other hand, spoke to him. “It had an economy to it, an honesty,” Cabella says. Plus, it wasn’t yet popular to collect. In fact, most of his early finds were castoffs, found in dusty thrift stores or forgotten in basements. “I was trying to show that 30-year-old stuff was still relevant.”

Indeed, it continues to speak. “Objects hold stories,” Cabella says. “But you need to take time to sit and study each detail. You need the heart to pay attention.”

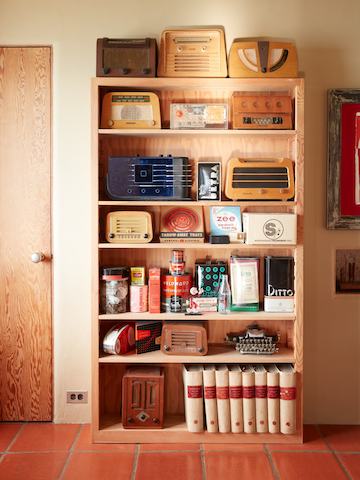

Take the circular sound holes backed by perforated Masonite cut in the face of a 1946 plywood radio. “They’re figuring out the technology of molded plywood,” Cabella says. “These circles show up again and again,” eventually as dimples on the ESU’s plywood doors. That Eames-designed radio is one of many rarities lining the wall of Cabella’s office. He points at the radios like family photos on the fridge door: “This is Eames. This is Eames. Girard. Eames. This might be Eames but I haven’t listened to it yet.” He means listened to its story—not the Giants game. “Oh they work, but I’m half deaf. If I listen, I listen to jazz. It’s timeless.”

Of all the treasures washed through Cabella’s store and home, his favorites are the prototypes. “Seeds of ideas,” he calls them. In his bedroom is one of George Nelson’s prototype dressers from 1949 or 1950. As Cabella tells it, Nelson and the Eameses were playing with aluminum, newly available (and cheap) from the war’s aircraft industry. In this early version of the Steelframe chest for Herman Miller, Nelson used aluminum for the handles. “The Eameses are using aluminum from a mechanical, engineering perspective,” Cabella says. “Nelson uses it as something organic. Feel that!” Curved just enough to fit your thumb and coolly, unnaturally soft, the handles feel like ocean-tumbled glass, something solid straining back toward the sea. The aluminum was dropped in favor of starker steel for what eventually went into production. “It was too elegant,” Cabella says. “Four or five years ahead of schedule. Now, the dresser’s an orphan.”

Cabella prefers prototypes, including a Nelson-designed dresser. They give insight into a designer’s process.

"Authenticity is a kind of respect."

The dresser, and other orphans like it, have found a home here with Cabella. “I’m the third owner of this house,” he says, walking down from the patio to a small wave-lapped porch with a view of Tiburon and Angel Island. “When the woman who lived here before me asked what I thought of her million dollar view, I said, ‘I don’t care about the view!’ And we just sat for hours and talked. That’s my food.”