New Yorker and nascent industrial designer Gilbert Rohde walked into Herman Miller’s Grand Rapids showroom looking for work in July 1930. The country was in the midst of the Great Depression and the company was on the verge of bankruptcy. Following a trip to Europe in 1927, Rohde returned with Bauhaus-inspired ideas that better suited contemporary architecture and lifestyles in America. Inspired by his former Stuyvesant High School classmate Lewis Mumford, whose writings made ideas about architecture and cities more accessible, Rohde sought to produce modern furniture not just for wealthy private clients, but for everyone.

Why Magazine

Designer Gilbert Rohde and the transformation of Herman Miller

As Herman Miller's first-ever design director, Gilbert Rohde's ideas modernized the furniture industry, from product design to the way we sell furniture.

“The most interesting thing in the home is the people who live there,” Rohde told De Pree. “I’m designing for them.”

In his sales pitch to Herman Miller founder D.J. De Pree, Rohde preached the importance of human-centered design. “The most interesting thing in the home is the people who live there,” Rohde told De Pree. “I’m designing for them.” Described as a “vivid and persuasive talker,” in a 1944 obituary from Interiors magazine, Rohde convinced De Pree to take a risk and shift Herman Miller’s business entirely, transforming the company into the juggernaut it is known as today. Gone was the focus on antique reproductions, replaced by problem-solving modern furniture, the likes of which had never been seen in a West Michigan woodshop.

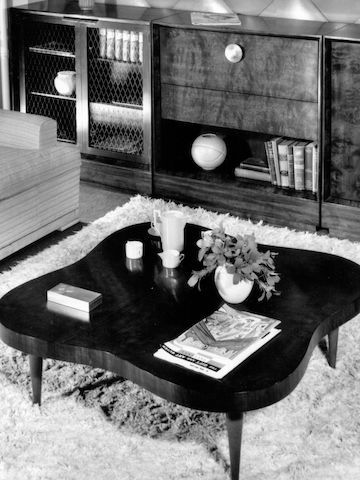

At Herman Miller, Rohde demonstrated the impact that design could have on operating a business. He consulted not only on product design, but also evolved manufacturing processes and taught the company how to sell by producing the first catalogs and showrooms devoted to modern furniture. He catapulted the West Michigan company to the global stage at the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair by furnishing the bedrooms of the Design for Living House with modular and clean-lined case goods. Seen by millions at the fair, Rohde’s designs also garnered coverage in magazines like House Beautiful and DOMUS. The seeds were planted and Rohde’s ideas of modularity and pursuit of material and manufacturing innovation remain at the center of Herman Miller’s business.

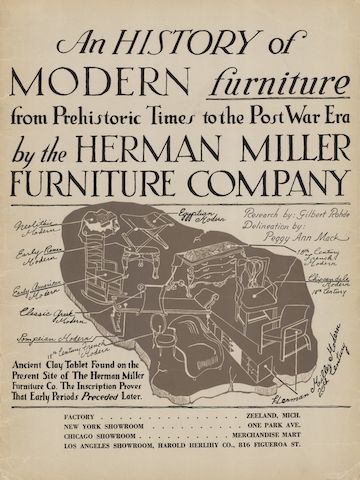

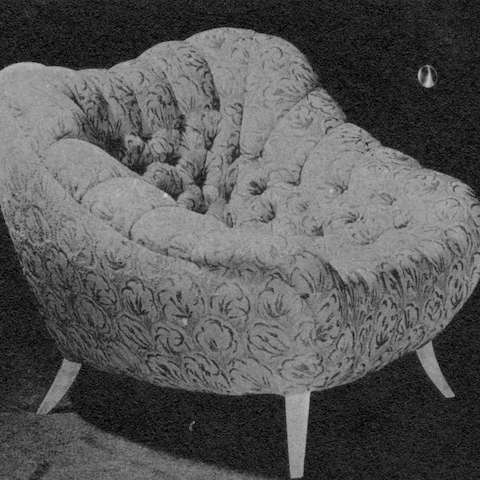

From 1936 until his sudden death in 1944, Rohde collaborated with Peggy Ann Mack, an artist and industrial designer who trained at Pratt Institute and the Design Laboratory, a tuition-free design school started by the Works Progress Administration and headed by Rohde. Mack was hired into Rohde’s office and worked on showroom, exhibition, and product design. She is named as the illustrator of striking and biomorphic Herman Miller modern catalog designs from 1941. Mack and Rohde also married that year. During her time in the studio, furniture design shifted from strictly rectilinear and modular and evolved to incorporate organic shapes that were emerging in contemporary art and would later define midcentury modern design.

Rohde’s genius lay in his polymath interest in culture at large. Prior to industrial design, he spent time as a music and drama critic, a cartoonist, and a fashion illustrator. His skill at perceiving changes in society allowed Rohde to anticipated people’s needs.