You probably don’t know Ray Wilkes, the person, as much as you recognize #raywilkes, the hashtag. The latter is usually paired with a photo of Wilkes’s most enduring design, a modular seating system that looks uniformly cheerful with its distinctive, rounded silhouette. You may also spot a #raywilkes in the wild, as I did when I found an Instagram post by a vintage dealer in the Bay Area, who had scored a pair of hefty chrome chair bases off the designer himself a few years ago. The bases are unusual, and rare—they were only prototyped for Herman Miller, never in production—and I was intrigued.

Chances are, I’m not the only person curious to know more about Ray Wilkes, now that Herman Miller has reissued his iconic Modular Sofa Group—dubbed “Chiclet”—for a new generation.

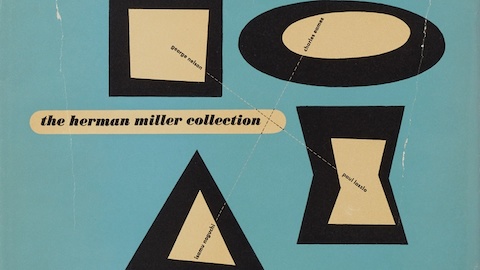

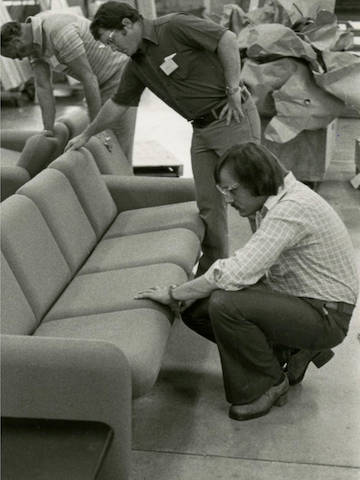

Herman Miller promotional photography, circa 1975.

As it so happens, Ray Wilkes the person is 85, living in Southern California, and possessed with a keen memory for detail. He recalls the address of George Nelson’s Manhattan office (50th Street at 5th Avenue) when Ray first arrived in the U.S. on a study grant from the Royal College of Arts. He remembers the precise Herman Miller catalog (Action Office I, 1964, with a green cover) to which he contributed drawings, in collaboration with fellow Nelson Office alum Tomoko Miho.

As Lance Wyman—another friend and colleague from the Nelson days—attests, Wilkes is “always sharp as a tack and very witty.”

A witty Brit in Michigan

“The fact is, I like total simplicity,” says Ray Wilkes. “It’s the philosophy of my life. An architect once told me that I was a true minimalist. And minimalism isn’t just straight lines—the most important thing is the form, and the simplicity of making it.”

That perspective has driven all of Wilkes’s work, but most notably the development of his Modular Sofa Group. After he arrived in Michigan to work full-time at Herman Miller, under then-design director Bob Blaich, Wilkes started experimenting with a new toy in the manufacturing area of the plant: a machine for injecting foam into a mold. “At first they were trying to apply the machine to Eames furniture, and then I was asked how it could be used,” he recounts. Having learned the gist of the technology after a stint with designer Harvey Probber in Rhode Island, Wilkes had figured out how to avoid getting air bubbles into the foam.

The molded forms he came up with were “all rounded, and it was possible to upholster them with Herman Miller’s two-way-stretch fabrics, seamed around the edge of the cushion—which would be very hard with traditional cloth.” That very distinctive cushion shape spawned a popular nickname for the collection that’s still common today: Chiclet.

On first glance, his design may seem like a stylistic departure from the Herman Miller classics, but Head of Archives and Brand Heritage Amy Auscherman points out that “it’s a modular system, and Herman Miller excels in systems."

Similarly, Herman Miller has a long track record of material and furniture innovation, typified by the Eameses’ molded plywood group and going all the way back to Gilbert Rohde, who invented the sectional sofa. "Chiclet is another way to get at that idea with new materials and a different aesthetic,” explains Auscherman. “It looks postmodern, but it’s timeless, because it’s pared down to the essentials.”

Problem-solving design, from the sling to soft seating

After Wilkes obtained his degree in furniture design from London’s Royal College of Art—with first-class honors, as he is quick to point out—he arrived in New York with his eyes on one prize: Working in George Nelson’s studio. He joined the team of designers (the aforementioned Miho and Wyman, as well as Hilda Longinotti, Ron Beckman, Bill Cannan, Irving Harper, and others) and was conscripted into troubleshooting a new piece of furniture: the Sling Sofa.

“I was given the responsibility of making it work once they had the design. They were having problems with the upholstery where it attaches to the frame, so I did some research," Wilkes recalls. “There was an English company that made rubber sheeting, so I attached that instead of webbing under the cushions. George told me, ‘Thank you, kid’—because I helped him get the sofa into MoMA.”

After three years at George Nelson & Associates, Wilkes returned to Britain, then boomeranged back to the United States—first to Rhode Island, where he worked for a time with Probber, and then on to Michigan, when he was recruited to a full-time position with Herman Miller. The Miller years were fruitful both creatively and personally—Wilkes met his wife, Anitra Seitamo, a Finnish designer who worked on the company’s showrooms, while on the job.

Several of his prototypes for the company never made it into distribution. Wilkes describes a desking system made of wood—an “alternative to Action Office, which was very bland to me.” His ideas proved challenging to execute during the mid-1970s, given the focus on the new office landscape. “The marketing department was always zipped up with Action Office II, doing [task] seating with mesh, not upholstery. All the energy in the company was in that area."

Nonetheless, Wilkes’s designs from the period stand out as prescient: early precedents of the pillowy upholstered forms so popular today, with a dose of ’70s jocosity. There’s the Soft Seating from 1974, a collection of upholstered chairs that expressed “a generous scale [and a] soft surface concept indicative of supreme comfort" and were set atop chrome bases that concealed casters underneath.

And then there’s the Rollback Chair (1977), which, as the New York Times described in its NeoCon coverage that year:

The outsized sausage—it’s about the size of a giant roll of paper toweling—permits the user a choice of seven backrest positions, adjustable in a 70-degree arc. The bearded British designer rolled the chairback through its positions easily but took several minutes to raise the seat to a proper height.

“It takes a bit of doing,” he acknowledged impatiently, as he made himself comfortable swinging around in a full circle and straddling the chair as one would a horse. “The original design had an air device that would have simplified moving it up and down. There are production problems to be conquered on that, but the feature is coming.”

One additional Wilkes piece that did make it into distribution was a flatpack coffee table to accompany his Modular Sofa Group. It's extremely simple, and exceedingly satisfying: a top, metal plate with clips that snap on the bottom, and bent legs.

One might marvel at the fact that Chiclet has made such an impression on vintage collectors in the decades since its release in 1976. Wilkes is delighted at the sofa’s continued relevance, though not necessarily amazed: “The design is so basic it’s timeless.”

What was introduced as an ancillary product essentially intended for office building lobbies is comfortable enough, and versatile enough, to work in almost any domestic space. Originals, usually of the two- and three-seater variety, tend to sell as soon as they listed through shops like Bi-Rite Studio, Home Union, and Circa Modern. As Auscherman—who found her own vintage Chiclet armchair and loveseat via Craigslist when she moved to Michigan to join Herman Miller—puts it: “Our most successful, enduring products have always performed well in any context, because they’re good design.”