Ray and Charles Eames took child’s play seriously. They invented playthings, furniture, and films to spark, but never limit, the young imagination. Given their own ideas of fun, these toys tended to emphasize composition, structure, and building, giving children the tools of their own adult trades in miniature (and giving some adults the chance to make like children again). Many of their designs embrace what kids and parents have long known: that the box an item comes in, especially if it’s a very large item, can be more exciting than the contents.

Set up in what appears to be the parking lot outside the Eames Office, Carton City apes the fictional community of Mayberry, with stop signs, neighborly visiting, even miniature landscaping (top). Dotted lines printed onto the Eames Storage Unit shipping cartons indicate ideal locations for the entrance and windows with awnings, 1950 (bottom left). Sun-kissed kids play in Eames Alley and Miller Street (bottom right). © Eames Office, LLC

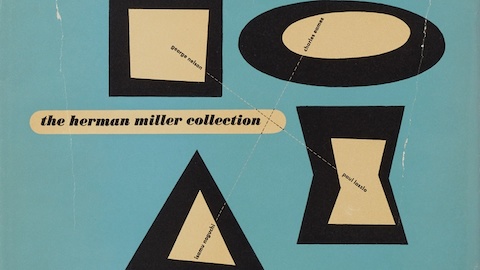

So it comes as no surprise that the Eameses improved the box itself, as a portfolio of photographs unearthed from the Herman Miller Archives reminds us. The humble cardboard box offers children their first chance to make space for themselves, whether that’s a racecar, a robot, or a house, sprouting from the shipping container the Eames Office designed in 1951 for the Eames Storage Units (ESUs).

“Printed in a colorful red and black design, and featuring the distinctive Herman Miller ‘M,’ the heavy cardboard carton, reinforced with wood splines, had only to be re-nailed to the bottom wood skid, after the furniture had been removed, to be made into a playhouse youngsters would love,” reads text from a draft press release. A separate leaflet offers instructions on “How to Make a Playhouse,” but it should have been self-explanatory: dotted lines suggest locations for an entrance and a view out, as well as jaunty awnings.

This town’s park bench is one of the Eameses’ molded plywood stools, made by Evans Products in 1945. © Eames Office, LLC

In one fell swoop, the Eameses managed to combine adult and child fun, eliminate waste, and add excitement to the mundane process of delivery. The up arrows, as well as the deep V of the logo “M,” designed by Irving Harper for the company, suggest the possibility of upward expansion into a miniature townhouse or skyscraper, should a child or parent need more furniture.

The ESUs themselves were also a kind of demountable toy for grownups. Made of perforated steel extrusions with diagonal bracing, they could be configured as low credenzas or high bookshelves. Buyers could customize the interior arrangement, selecting plywood drawers or doors, and perforated metal or enameled Masonite filler panels. Owners could also take them apart and rearrange or add on, treating the furniture as a series of modular boxes‑ furniture as toy.

This plan of the Eames Office room display, created by Ray Eames for An Exhibition for Modern Living in 1949, exemplifies the designers’ playful approach. Photo courtesy of Andrew Neauhart.

As adults designing playthings intended for children, the Eameses found more inspiration in boxes. The Toy, manufactured by Tigrett Enterprises in 1951, offered children the chance to make their own prefabricated structure, one more colorful and flexible than Carton City. The Eameses had first been in touch with Tigrett about manufacturing large, bright, paper-and-cardboard animal masks based on those they used for skits and photo shoots in the late 1940s. The Memphis-based company was run by the highly entrepreneurial John Burton Tigrett, who made his fortune selling the Glub-Glub duck and may have been looking for more patentable products. The masks never made it out of the prototype stage, but the simpler and more geometric Toy did.

The Toy combined thin wooden dowels, pipe cleaners, and a set of square and triangular stiffened-paper panels in green, yellow, blue, red, magenta, and black. Children could run the dowels through sleeves on the edges of the panels to strengthen them, and then attach these struts at the corners. Initially sold in a big, flat box via the Sears catalog, the Eameses soon redesigned this packaging as well, creating a far more elegant 30-inch hexagonal tube, into which all parts could be rolled and stored.

The first version of the Toy made spaces big enough for children to inhabit, like the cartons. The Little Toy, released in 1952, was scaled more like an architectural model, allowing children to radically reinterpret the dollhouse. (The office later prototyped a modern model house for Revell, but it never went into production.) The Little Toy boxes, which feature a grid of colorful rectangles and words, resemble the panelized arrangement of the Eames House façade and the ESUs, and all of these products, at their various scales, were being developed at the Eames Office within the same few years.

The smaller scale of The Little Toy (top left) allowed children and adults to create their own architectural models (top right, bottom), 1952. © Eames Office, LLC

Charles Eames once said of the work done out of the Eames Office, “We work because it’s a chain reaction, each subject leads to the next.” The connection to the ESU cartons and The Toy is immediately apparent in the longest-lived of the modular, paper-based playthings to come out of the Eames Office, the House of Cards.

House of Cards originally came as two decks of 54 cards, with two slots on each side and one on the ends. As with The Toy and Little Toy, the idea was to make construction of space as easy as possible. The notches more elegantly solve the problem of connections: no more dowels or wire frames, and no tools. In their house and the ESU, mix-and-match stopped at texture and hue. On the cards, players got to choose 54 different patterns for the first deck, and 54 different photographs for the second.

The photographs and patterns on the House of Cards (left) were chosen with much deliberation, intended to illustrate common objects like scissors, buttons, lockets, and lace whose everyday beauty might be overlooked. Tin cars and tin trains also appear, five years before they would be animated in the Eames film “Toccata for Toy Trains.” The notches on House of Card made them easier than The Toy to build with, as Charles Eames demonstrates (right), 1952.

© Eames Office, LLC

The Tigrett catalog for all three Eames products noted, “This group of toys has been happily received by parents and educators because they make available real color and real space through three construction systems of three greatly different sizes, all different and all brilliant.” The illustrations on House of Cards give any structure you make the look of a multi-screen media event—another idea the Eameses would explore.

In the voiceover for “Toccata for Toy Trains,” Charles Eames says, “In a good old toy there is apt to be nothing self-conscious about the use of materials. What is wood is wood; what is tin is tin; and what is cast is beautifully cast.” He could have added, in reference to the couple’s own toys, what is cardboard is cardboard, and then talked about the qualities that make it an ideal building material: its strength, its low cost, its ability to withstand a judicious number of cuts and slots.

Cardboard offers an opportunity for a child’s first attempts to build and, with Carton City, the Toys, and the Houses of Cards, Ray and Charles Eames indeed offered a prelude to the more serious (or at least more adult) explorations of structure and material they embarked upon with houses, showrooms, and furniture. Cardboard, the substance of prototypes and animal masks, also comes into your house without designer packaging. Seeing its potential connects Charles and Ray to the diminutive, imaginative world—a world in which any box contains a city.