Steve Cabella’s Monark bicycle leans against a concrete block wall outside his home, a William Wurster-designed single-storey residence on the edge of San Francisco Bay. The house and the bike are the same age – built in 1935 – and both work just fine. “It goes, it turns, it stops – of course, I still ride it,” he says.

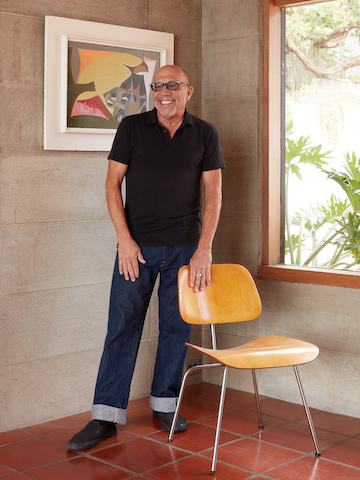

A voracious and long-time collector, Cabella spends his time digging through archives and organising exhibitions – 12 and counting like “Ray and Charles in Hollywood,” about the Eameses’ connections to the film industry. The Modern i, his furniture outpost in San Anselmo, north of San Francisco, was a destination for mid-century modern fans. He closed the physical location in San Anselmo, but he keeps collecting stories. As the tide laps against the seawall underneath, Cabella tells one about his bike, and his favourite material, aluminium.

“I love aluminium,” Cabella says. “Monark used aircraft-grade aluminium tubes – it was what was available at the time. It was easy to get, it’s honest, simple, malleable. It can be anything you want but it always looks like what it is.” He looks at the bike for a bit, the low maritime sun flashing off the polish. “I like it for the same reasons they like it.”

At Cabella’s house, the past is present. The collector has decked it out in mid-century modern gems from his personal archive. “They” are iconic designers the likes of George Nelson, Charles and Ray Eames, and Alexander Girard. He talks about them in the present tense, and their spirit is palpable, a reverberating echo like the waves beneath the house. Cabella has spent his life listening to voices few others hear.

He started collecting early, going to flea markets as a teenager looking for good design, or good stories, or anything other than the austerity of his childhood. Cabella was always a few decades behind – in the late sixties, he was dressing Victorian, lining his room in turn-of-the-century fabrics, throwing parties where correct period attire was enforced “down to the watch in your pocket.” His high school yearbook photo shows a young man dressed like a nineteenth-century dandy. “Authenticity is a kind of respect.”

“Objects hold stories. But you

need to take time to sit and study

each detail. You need the heart to

pay attention.”

By the late seventies, when he opened his shop, the Modern i, Cabella was exploring Art Deco. It was trendy to collect at the time, and had an appeal – “strong aesthetics is an instant story.” But Art Deco was expensive; its classy curves reserved for those who could afford them. “It wasn’t for people like me.”

The 1935 house, designed by William Wurster (namesake of the architecture school building at nearby University of California, Berkeley), overlooks the San Francisco Bay towards Marin.

Mid-century modern design, on the other hand, spoke to him. “It had an economy to it, an honesty,” Cabella says. Plus, it wasn’t yet popular to collect. In fact, most of his early finds were cast-offs, found in dusty second-hand shops or forgotten in cellars. “I was trying to show that 30-year-old stuff was still relevant.”

Indeed, it continues to speak. “Objects hold stories,” Cabella says. “But you need to take time to sit and study each detail. You need the heart to pay attention.”

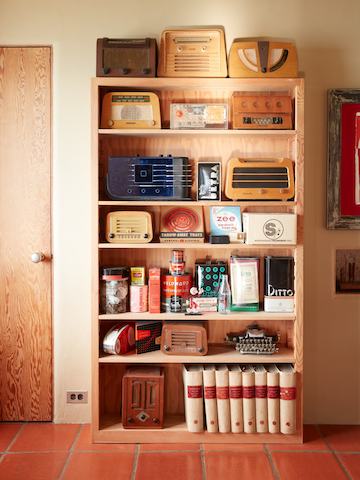

Take the circular sound holes backed by perforated hardboard cut in the face of a 1946 plywood radio. “They’re working out the technology of moulded plywood,” Cabella says. "These circles show up again and again," eventually as dimples on the Eames Storage Unit (ESU) plywood doors. That Eames-designed radio is one of many rarities lining the wall of Cabella’s office. He points at the radios like family photos on the fridge door: “This is Eames. This is Eames. Girard. Eames. This might be Eames but I haven’t listened to it yet.” He means listened to its story – not the San Francisco Giants baseball game. “Oh they work, but I’m half deaf. If I listen, I listen to jazz. It’s timeless.”

Of all the treasures that washed into Cabella’s shop and home, his favourites are the prototypes. “Seeds of ideas,” he calls them. In his bedroom is one of George Nelson’s prototype dressers from 1949 or 1950. As Cabella tells it, Nelson and the Eameses were playing with aluminium, newly available (and cheap) from the wartime aircraft industry. In this early version of the Steelframe chest for Herman Miller, Nelson used aluminium for the handles. “The Eameses are using aluminium from a mechanical, engineering perspective,” Cabella says. “Nelson uses it as something organic. Feel that!” Curved just enough to fit your thumb and coolly, unnaturally soft; the handles feel like ocean-tumbled glass, something solid straining back towards the sea. The aluminium was dropped in favour of starker steel for what eventually went into production. “It was too elegant,” Cabella says. “Four or five years ahead of schedule. Now, the dresser’s an orphan.”

Cabella prefers prototypes, including a dresser designed by George Nelson. They give insight into a designer’s process.

"Authenticity is a kind of respect."

The dresser, and other orphans like it, have found a home here with Cabella. “I’m the third owner of this house,” he says, walking down from the patio to a small wave-lapped porch with a view of the Tiburon Peninsula and Angel Island. “When the woman who lived here before me asked what I thought of her million-dollar view, I said, ‘I don’t care about the view!’ And we just sat for hours and talked. That’s my food.”