Designer and sculptor Isamu Noguchi once defined the essence of sculpture as “the perception of space, the continuum of our existence”. For Noguchi, everything was sculpture, and in Martha Graham – perhaps America’s most important modern dancer and choreographer – he found the perfect collaborator. Their partnership as choreographer and set/prop/costume designer spanned three decades, and together they produced 18 original dances, including Graham masterpieces such as Appalachian Spring (1944), Night Journey (1947) and Phaedra (1962). Graham’s school of movement is violent, beautiful and strange, and while inhabiting Noguchi’s quiet, suggestive sets, she used it to explore a mythological landscape: Greek, Biblical, American. If Graham’s dances helped to reimagine a modern body in space, then it was Noguchi who concerned himself with the stage itself. Spare, abstract and essential, Noguchi’s sets could be as simple as a line of rope for Frontier (1935), or as foreboding and complex as the cage-like metal dress he designed for Cave of the Heart (1946). “I felt that I was an extension of Martha and that she was an extension of me”, Noguchi once said. Here are the two artists in their own words.

A curious intimacy exists between artists in a collaboration. A distant closeness. From the first, there was an unspoken language between Isamu Noguchi and me. Our working together might have as its genesis a myth, a legend, a piece of poetry, but there always emerged for me from Isamu something of a strange beauty and an otherworldliness.

–MARTHA GRAHAM

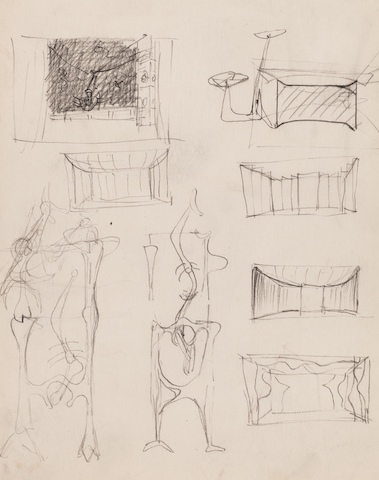

I made a head of the great dancer Martha Graham soon after I got back to America [in 1929]. At that time, she was not known, but she lived around the corner from Carnegie Hall, near where I had a studio, so I used to go and watch her classes. There were many pretty girls there, and I would draw them.

–ISAMU NOGUCHI

The first collaboration Isamu and I worked on was Frontier, in 1935, and we would continue to work together for the next fifty years. Our collaboration ended in December 1988, on the day that Isamu died; we were then still working on projects for the future. As was our way, we looked to the act of becoming, not to the past.

–GRAHAM

Usually she called me up in the dead of night and said, ‘Isamu, I need your help and I have a wonderful idea and I want to tell you about it’. I’d go over there and she would go into a story about what she wanted to do…And then I’d go home and I’d give her the setting that would encompass such an emotional topic.

–NOGUCHI

Sometimes I would get bumps on my arms because I would see Martha and Noguchi fighting each other, the two of them, because they were so much into what they were doing. ‘Get out of here’, they would scream. Isamu would come the next day and they would make up. In art, they were like wife and husband.

–TAKAKO ASAKAWA, FORMER DANCER IN THE MARTHA GRAHAM COMPANY

When I needed a bed for Night Journey I asked Isamu Noguchi to bring me a bed and he did, quite unlike any bed I had ever seen before. It is the representation of a man and a woman – nothing like a bed at all.He brought to me the image of a bed stripped to its bones, to its very spirit.

Isamu created his work mainly from some idea I gave him or some idea he gave me. I would perhaps give him the bones of an idea and he would return with something whole. I never told Isamu what to do or how to do it. He had a great feeling for space and its use on the stage.

When I needed a place for Medea onstage, the heart of her being, Isamu brought me a snake. And when I brooded on what I felt was the insolvable problem of representing Medea fleeing to return to her father the Sun, Isamu devised a dress for me, working from vibrating brilliant pieces of bronze wire that became my garment and moved with me across the stage as my chariot of flames.

–GRAHAM

Isamu Noguchi and Martha Graham’s extended collaboration perpetuated in America [Ballets Russes founder Sergei] Diaghilev’s belief in using visual artists’ designs for dance. Two of today’s most influential modern choreographers, Merce Cunningham and Paul Taylor, were members of Martha Graham’s company, and both were inspired and influenced by Graham’s long-running artistic relationship with the sculptor. Each has actively sought to involve visual artists in the designing of his dances. The most obvious collaborations in this lineage are Cunningham with Robert Rauschenberg and Taylor with Alex Katz.

–ROBERT TRACY, DANCE WRITER

A dialogue with the audience is what Martha is having. I’m having a dialogue with the environment…Martha in her use of my sets enriched the meaning. I have suggested something, but she specifically puts it into experience. It is a new experience. It is also part of the sculptural experience.

–NOGUCHI

I believe that the genius of their collaboration was that they found a way to make it perpetual. Their artistic partnership did not end with the completion of the set and the premier of the choreography. The interaction between these two artists continues to this day. It exists wherever a Martha Graham dancer and an Isamu Noguchi set rehearse together, challenging and inspiring each other to have increasing impact on their next audience.

–JANET EILBER, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR OF THE MARTHA GRAHAM DANCE COMPANY

Everything he does means something. It is not abstract except if you think of orange juice as the abstraction of an orange. Whatever he did in those sets he did as a Zen garden does it, back to a fundamental of life, of ritual. I forget who said it, but Noguchi illustrates the ‘shock of recognition’.

–GRAHAM

There is joy in seeing sculpture come to life on the stage in its own world of timeless time. Then the air becomes charged with meaning and emotion, and form plays its integral part in the re-enactment of a ritual. Theatre is a ceremonial; the performance is a rite. Sculpture in daily life should or could be like this. In the meantime, the theatre gives me its poetic, exalted equivalent.

–NOGUCHI